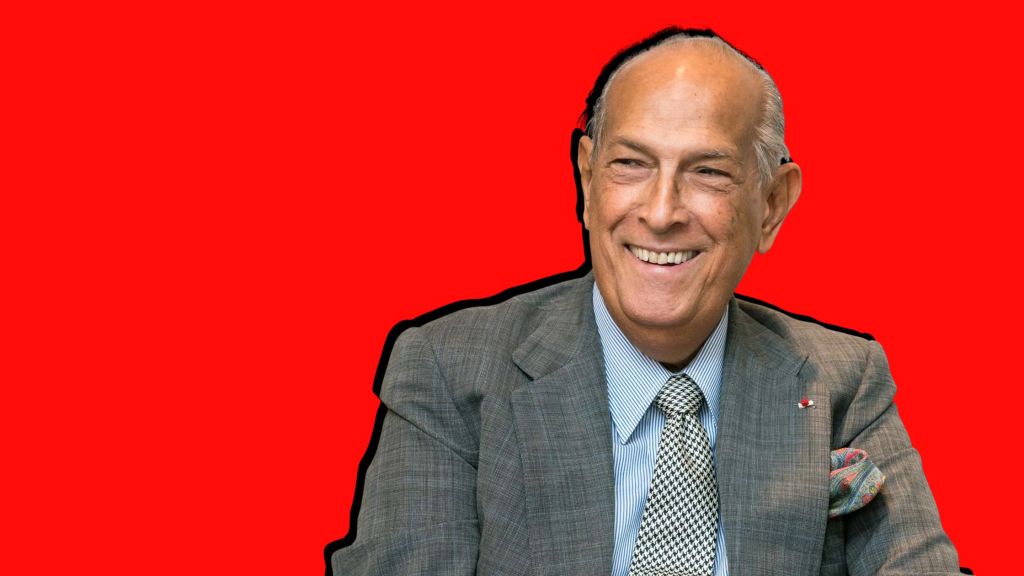

Oscar de la Renta: Dressing Power, Grace, and Ceremony

Early Life in the Dominican Republic

Oscar de la Renta was born on July 22, 1932, in Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic. He was the youngest of seven children in a respected middle-class family. His father worked in insurance, and his mother came from a prominent Dominican lineage with deep cultural roots. The household emphasized education, manners, and presentation.

Growing up in the 1930s and 1940s under the regime of Rafael Trujillo, de la Renta witnessed a society where public image carried weight. Santo Domingo was socially formal and tightly structured. Elite families participated in diplomatic and cultural circles where dress signaled status and refinement. Although he would later build a career in New York and Paris, the codes of elegance he absorbed in the Caribbean remained foundational.

As a child, he showed talent in drawing. Fashion was not yet his intended path. He initially planned to become a painter. At 18, he left the Dominican Republic to study fine arts in Spain. That decision began a journey that would eventually reshape American fashion.

Madrid and the Shift Toward Couture

Fine Arts Education

In the early 1950s, de la Renta enrolled at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. His formal training in painting and composition gave him discipline and technical control. He learned proportion, balance, and the study of historical aesthetics.

Madrid also exposed him to European social life. He began sketching dresses for society women, gradually discovering that fashion combined artistry with practicality. Clothing moved. It existed in public spaces. It carried symbolic power.

Apprenticeship with Cristóbal Balenciaga

A defining early step came when he apprenticed under Cristobal Balenciaga. Balenciaga was widely regarded as a master technician whose silhouettes were sculptural and innovative. His atelier operated with strict discipline and intense attention to construction.

Working alongside Balenciaga introduced de la Renta to couture craftsmanship at its highest level. He observed how internal structure shaped external form. He learned restraint. He learned that elegance often came from precision rather than excess.

Balenciaga was not demonstrative with praise, but his influence was lasting. De la Renta later acknowledged that much of his understanding of proportion and architectural thinking came from these formative years.

Paris and Lanvin

After Madrid, de la Renta moved to Paris. He joined the couture house of Lanvin, working under designer Antonio Castillo. In Paris, he refined his understanding of luxury ready-to-wear and the business mechanics of haute couture.

Paris in the late 1950s was still the epicenter of global fashion. Yet the industry was beginning to shift. American fashion was gaining independence, and New York was emerging as a powerful market. De la Renta sensed opportunity there.

Arrival in the United States

Elizabeth Arden and the American Market

In 1963, de la Renta moved to New York to design couture for Elizabeth Arden. This marked a significant transition. Unlike Paris, New York prioritized practicality and commercial viability. American women wanted glamour, but they also wanted mobility and function.

De la Renta adapted quickly. His designs blended European sophistication with American ease. He understood that American clients valued polish but disliked excessive rigidity. This balance would become central to his brand.

Launching His Own Label

In 1965, he launched his own ready-to-wear label under his name. Establishing an independent house required financial risk and strategic positioning. Unlike many designers who leaned into avant-garde experimentation, de la Renta focused on refined femininity.

His early collections featured tailored day suits, evening gowns with fluid movement, and detailed embellishments that reflected his heritage. He integrated embroidery and rich textures without overwhelming the silhouette.

The timing worked in his favor. The 1960s were a decade of social upheaval, but elite social life remained influential. Society hostesses, philanthropists, and political figures sought designers who embodied grace rather than rebellion. De la Renta filled that space.

The 1970s: Establishing an American Signature

During the 1970s, de la Renta solidified his role as one of America’s leading designers. His clothing projected optimism and polish. He embraced bold prints, vibrant color, and fluid eveningwear.

Unlike minimalist designers who emerged later in the decade, de la Renta maintained a decorative sensibility. His Dominican background influenced his use of color and texture. At the same time, his tailoring remained structured and precise.

His clientele included socialites and public figures. Among the most notable was Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Dressing Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis positioned him within the highest circles of American cultural life. Her choice of de la Renta reinforced his association with elegance and diplomacy.

Throughout this period, he expanded into fragrance, recognizing the importance of brand diversification. Licensing agreements allowed him to grow financially while maintaining couture prestige.

The 1980s: Power Dressing and Global Expansion

The 1980s introduced a different aesthetic climate. Corporate culture intensified. Women entered executive spaces in greater numbers. Fashion shifted toward assertive silhouettes.

De la Renta responded without abandoning his core identity. He incorporated stronger shoulders and sharper tailoring while preserving femininity. His evening gowns remained romantic but gained structural clarity.

He also strengthened his presence internationally. His designs were sold in major department stores and boutiques worldwide. Unlike some European houses that struggled with American mass-market demands, de la Renta navigated licensing strategically.

In 1989, he became the first American designer to lead a French couture house when he was appointed creative director of Balmain. This move demonstrated his international credibility. Leading Balmain required balancing heritage with renewal. He respected the house’s traditional codes while modernizing its silhouettes.

His tenure at Balmain lasted until 2002. During those years, he commuted between Paris and New York, reinforcing his transatlantic influence.

Leadership and Industry Influence

Beyond design, de la Renta played a central role in shaping the American fashion industry’s institutions. He served as president of the Council of Fashion Designers of America from 1973 to 1976 and again from 1986 to 1988.

Under his leadership, the CFDA expanded its organizational structure and strengthened industry recognition. He supported emerging designers and advocated for professionalism within American fashion.

He also contributed philanthropically. In the Dominican Republic, he funded schools and charitable initiatives. His ties to his birthplace remained active throughout his life. In Punta Cana, he helped support educational and community development programs.

The 1990s: Red Carpet Authority

By the 1990s, red carpet culture had become a major marketing platform. De la Renta emerged as a dominant presence. Actresses frequently selected his gowns for award ceremonies. His work projected classic glamour rather than shock value.

In a decade that saw minimalism dominate through designers like Calvin Klein and Donna Karan, de la Renta offered an alternative. His gowns were structured, detailed, and often embroidered.

He understood visibility. When celebrities wore his designs at events such as the Academy Awards, the exposure reinforced his reputation as a designer of occasion dressing.

Marriage and Personal Life

In 1967, he married Françoise de Langlade, a French Vogue editor who had significant influence within fashion circles. Their marriage connected him further to European cultural networks. She supported his career and helped shape his social positioning.

After her death in 1983, de la Renta later married Annette Engelhard in 1989. Annette had been married to American industrialist Charles Engelhard and brought her own social and philanthropic networks.

De la Renta and Annette adopted a son, Moisés de la Renta, in 1982. Fatherhood added a personal dimension to his otherwise disciplined professional life.

The 2000s: Continuity in a Changing Industry

The early 2000s marked a transition in fashion. Fast fashion accelerated production cycles. Younger designers embraced minimalism or conceptual experimentation.

De la Renta remained committed to craftsmanship. His collections continued to emphasize embroidery, lace, and structured eveningwear. Rather than chasing trends, he refined his signature.

He maintained strong relationships with American political families. Notably, Hillary Clinton and Laura Bush both wore his designs. His cross-party appeal reinforced his nonpartisan elegance.

In 2014, he designed the wedding gown for Amal Alamuddin when she married George Clooney. The gown, with its intricate lace and traditional silhouette, became one of the most discussed bridal designs of the decade.

Mentorship and Succession

As he aged, questions of succession became pressing. De la Renta valued continuity. In 2014, he appointed British designer Peter Copping as creative director. This decision signaled his intention to preserve the house’s aesthetic after his death.

Copping had previously worked at Nina Ricci and Louis Vuitton. His appointment demonstrated de la Renta’s commitment to maintaining craftsmanship while preparing for generational transition.

Illness and Final Years

De la Renta was diagnosed with cancer in 2006. He continued working throughout treatment, rarely allowing illness to dominate public narratives.

In interviews, he spoke candidly about aging and legacy. He believed designers should understand the women they dress. His perspective remained consistent: fashion was about dignity and beauty rather than provocation.

On October 20, 2014, Oscar de la Renta died at his home in Kent, Connecticut, at the age of 82. His death marked the end of a career that had spanned more than five decades.

Legacy

Oscar de la Renta’s legacy rests on synthesis. He bridged Europe and America. He combined couture technique with commercial strategy. He maintained decorative richness during eras that favored minimalism.

His influence extended beyond aesthetics. He professionalized American fashion institutions and demonstrated that designers could balance business growth with cultural authority.

In the Dominican Republic, he remains a national figure of pride. In the United States, he is remembered as a designer who dressed First Ladies, actresses, and generations of women seeking formal elegance.

His house continues to operate, preserving many of his codes: structured bodices, elaborate embroidery, and polished tailoring.

Oscar de la Renta did not position himself as a radical. He did not chase controversy. Instead, he built a reputation through consistency, discipline, and cultural fluency.

From Santo Domingo to Madrid, Paris, and New York, his trajectory reflected both ambition and adaptation. By the time of his death in 2014, he had become one of the most enduring figures in modern fashion history.